Community News

Commentary: The new Air Force hair standards exclude Black women

U.S. Naval Hospital Guam Public Affairs Office April 2, 2021

()

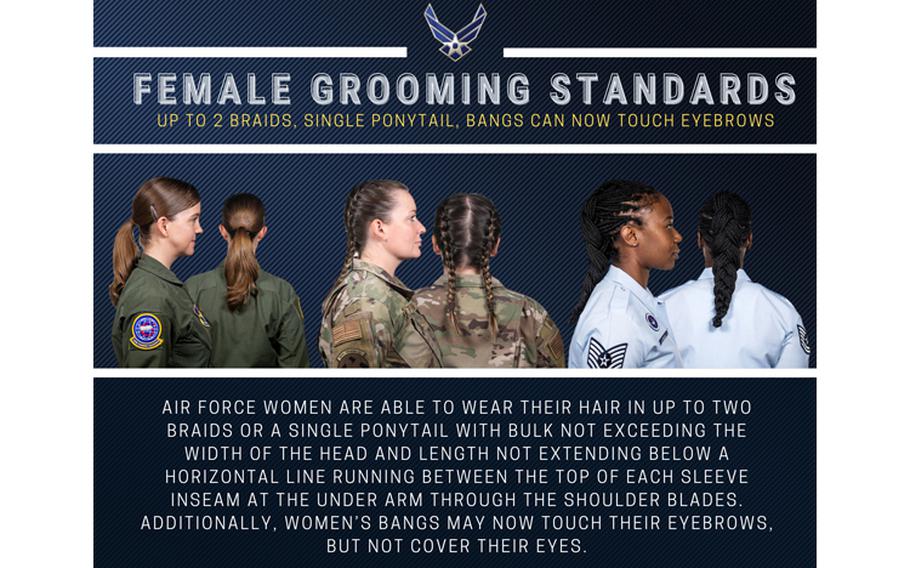

On February 10, new hair regulations for women in the U.S. Air Force went into effect. Air Force Instruction (AFI) 36-2903, Dress and Appearance of Air Force Personnel was amended to authorize new hairstyles, allowing female Airmen to wear hair past their shoulders in either a ponytail or up to two braids. Many praised the progressive approach to military dress and appearance, but in reality, the updated policy leaves behind a frequently forgotten group, Black women.

The Problem

To understand why the newly authorized hairstyles don’t go far enough to include Black women, a basic knowledge of hair type is essential. Hair type is primarily defined by curl pattern, falling into four major categories.

Type 1: Straight Hair

Type 2: Wavy Hair

Type 3: Curly Hair

Type 4: Coily Hair

Types 2-4 also have subcategories – A, B and C – that range from looser to tighter curls. For example, someone with Type 3A hair will have large, bouncy curls that form an S-shape. Black women most often are born with Types 3 and 4 curl patterns, 4C hair being the most fragile hair type with the tightest curl pattern. Type 4 hair is prone to breakage and, the curl pattern is difficult to style into prescribed military standards. Why? Because Type 4 hair grows differently. Straight and wavy hair grows downward from the weight of its length. Coily hair grows outward from the fullness of the curl pattern.

According to the Air Force press release regarding the updated policy, “Female airmen will be able to wear their hair in up to two braids or a single ponytail with bulk not exceeding the width of the head.” Type 4 hair is naturally “bulkier,” so low ponytails, braids and buns require high manipulation, which can be extremely damaging. Regardless, Airmen are required to maintain these styles for acceptance in professional environments and to avoid reprimands for not meeting regulations that unfairly exclude coily patterns.

Frankly, the new hair regulations do little to alleviate the pressure people of color feel to conform to Caucasian American beauty standards. Black female airmen will still need to alter or hide their natural curl pattern to achieve the new styles. Previous changes to the AFI allowed some Black hairstyles to be worn in uniform. This drove wigs, weaves, braids, locs, chemical relaxers and heat straightening to become common place for Black women in the military. However these styles, when used excessively, have been proven to cause traction alopecia, a prevalent form of hair loss in women of color, according to Dr. Crystal Aguh, a dermatologist specializing in hair loss and the co-author of Fundamentals of Ethnic Hair: The Dermatologist’s Perspective. Not to mention, braids and locs can cost upwards of $300 at the hair salon, take over six hours to create and require monthly maintenance equating to $100 or more. This is a pricey investment, which disproportionately burdens women of color, especially junior enlisted Airmen.

These styles are undoubtedly beautiful when done safely and women have every right to wear them if they choose. However, Black women who prefer to wear their natural curl pattern as-is also deserve regulation, complementary styles just like their straight and wavy hair counterparts.

I have Type 4A hair and struggle with appropriate hairstyles in uniform. My go-to hairstyle is the traditional low bun. The style takes me approximately 30 minutes, trying to smooth my curls with repetitive brushing and heavy hair products. Typically, my hair has reverted to standing straight up by 1600 hours, and I have subjected my roots to another day of rough treatment in the name of professionalism and military standards.

Airmen are taught in Basic Military Training, the Reserve Officer Training Corps, the United States Air Force Academy and Officer Training School (OTS) they should be able to accomplish hygiene and uniform standards in 15 minutes or less. A neat ponytail or braid is next to impossible to achieve with Type 4 natural hair in such limited time. This is why Black female airmen resort to the previously mentioned techniques. I paid a stylist to cornrow my hair prior to attending OTS to ensure I met the time constraints. The style cost over $100 dollars on top of an already expensive packing list required by the accessions program. The style was tight and damaging to my roots, but I opted for braids because my hygiene time was limited. I didn’t want to fall behind my flight members, so I left the style in longer than recommended. This led to significant hair loss. Sadly, some of the other Black women in the program cut their hair off before attending OTS because they knew they wouldn’t have time on a daily basis to safely style long hair into regulation military styles.

The Solution

Dress and Appearance Standards should be updated further for more inclusivity of Type 4 hair needs. First and foremost, Air Force leadership should eliminate the word “bulk” from the AFI. Even previous regulation stated hair could only have “a maximum bulk of 3 ½ inches from scalp and allow proper wear of headgear.” This term is also carried forward in the updated policy and hair is now authorized to extend up to four inches from the scalp.

“Bulk” ignores the way Type 4 hair typically grows and narrows the definition of acceptable styles to Caucasian standards. If hair was allowed to extend up to five inches from the width of the head, Black female airmen would have the room they need to style their hair safely and professionally. Air Force headgear comes in multiple sizes to accommodate the fullness of coily hair without forcing the strands from their natural state.

Headgear should also be optional for airmen not operating in combat zones or high-risk career fields such as Security Forces. The tradition of wearing covers in the military is one that caters to a predominately male demographic with short hair requirements. However, the battle uniform hat is not necessary or practical for airmen who work in office environments. Women, particularly women with Type 4 hair, struggle to maintain a neat appearance after continually replacing and removing their cover. What functional purpose does a hat serve when merely walking from the car to the threshold of the office building? Making hats optional for non-combat zones and low-risk career fields would alleviate the stress of maintaining another uniform item and a manageable hairstyle that lasts the duty day.

If “bulk” and hats were no longer a concern, more hairstyle options would be available. The “Wash ‘N Go” style – created by washing the hair, defining the curls with limited product and allowing it to dry naturally or with low, diffused heat – allows Black women to wear their natural curl pattern as-is and is considered one of the healthiest hairstyles for Type 4 hair. Another option is the “High Puff.” This style is the coily version of a ponytail, created by gathering the hair at the top of the head and securing with an elastic band.

I recently presented my concerns to the Department of the Air Force leadership and the Women’s Initiatives Team (WIT), an internal Air Force organization focused on researching women’s disparity issues within the service. The WIT advocated for the removal of bulk standards from the most recent iteration of AFI 36-2903. However, this section of their proposal was rejected. Since the publication of this article, the WIT is surveying Air Force personnel specifically in regard to hair type and sentiments around bulk restrictions. They will use their research to submit another proposal to the Air Force Uniform Board for consideration.

Standards and regulations are vitally important. AFIs contribute to good order and discipline and ensure there is a cohesive force dedicated to the common goal of serving. However, when regulations ignore a portion of a diverse work force, a career of sacrifice becomes even more challenging. If leadership is trying to reduce barriers, they should start by analyzing the unique challenges of Black female Airmen and include them in the Air Force’s version of progress.

Second Lieutenant Jasmine Mossbarger is an Air Force Reserve officer at Joint Base San Antonio Lackland and is a member of the 655th Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance Wing.

The views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Air Force, DoD or U.S. Government.